Building a framework for designing age-appropriate AI

The train for nuance seems to have left the station for social media. Can we preempt this panic when it comes to generative AI?

We’re a week delayed! Which I’m happy to say is due to a very busy May, full of great meetings, projects, conferences and presentations. Some more shareable moments:

I joined a panel on the history of trust & safety and where we go from here at the annual Marketplace Risk Management Conference in San Francisco

VYS presented some early work we’re doing on how content moderation needs to support evolving youth language at All Things In Moderation

The Cybersecurity Advisors Network, which I’m proud to support, published a call to action to combat technology-facilitated abuse and violence

I contributed to Duco’s Trust & Safety Market Research Report, which provides a comprehensive business case for investment in T&S

All that has meant jotting down notes for this monthly newsletter on a variety of modes of transportation. Still, sharing these insights and having a robust discussion about them afterwards is one of the very fulfilling parts of this role, so here is our somewhat massive May missive:

Debating youth wellbeing at the edges

Over the last two months, there has been an increasingly heated debate about the role of smartphones, social media, and the internet on children’s wellbeing. In March, The Anxious Generation by Jonathan Haidt quickly became a New York Times bestseller, arguing that the proliferation of smartphones led to “a great rewiring” and a new “phone-based childhood”. In response, an article in Nature by Candice Odgers argued that “there is no evidence that using these platforms is rewiring children’s brains or driving an epidemic of mental illness”. A new study from the Oxford Internet Institute authored by Matti Vuorre and Andrew Przybylski found instead “a positive correlation between well-being and internet use”.

As someone helping companies build more responsibly for young people, I’ve been glued to these arguments. I’ve pored over them for months, mapping them against what we know about the efficacy of product and policy protections for kids. My uneasy conclusion is that these discussions are currently destined to be debated at the edges, mainly because they both land on the same troubling (and in my view, incorrect) point: That there is no significant role for companies in supporting young people’s well-being.

We have seen this play out over the last 25 years, with a techno-libertarian approach absolving tech companies of significant responsibility for their products except the ones that they chose to take on. That has been amplified by the lack of access to longitudinal data from companies, a core need for independent researchers to truly understand whether products are causing harm.

With such minimal guidance for companies on how to best build and design products for children, we instead asked parents to play a greater role. For example, despite numerous reports on ranking recommendations leading children to harmful and inappropriate content, companies largely responded by increasing the suite of parental controls, only recently beginning to address how they more actively downrank and age-gate inappropriate content.

Cut to a global mental health crisis in 2024 (not just among youth populations), and we now seem headed towards techno-legal solutionism as critiqued by danah boyd, that reductively positions technology as the sole (or dominant) cause of mental health crises, recommending that society outright ban various forms of technology for children. It’s noteworthy, for example, that The Anxious Generation website calls for no actions from tech companies; only parents, educators, young people, and legislators.

Any argument that excludes the makers of technology from the conversation about youth well-being is fundamentally flawed. Techno-libertarianism may have worked when digital products weren’t ubiquitous, but now it’s impossible to ignore companies’ responsibility in building thoughtfully for young people, or to suggest that parents or educators hover over children’s near-constant exposure to technology. Our industry also has 25 years of data, progress, mistakes, and learnings to share with stakeholders to develop solutions together. Similarly, techno-solutionism overlooks the significant value technology, social media, and smartphones can have on adolescent well-being, especially when considering the global youth population, not just American or European experiences.

Can we get it right when it comes to generative AI?

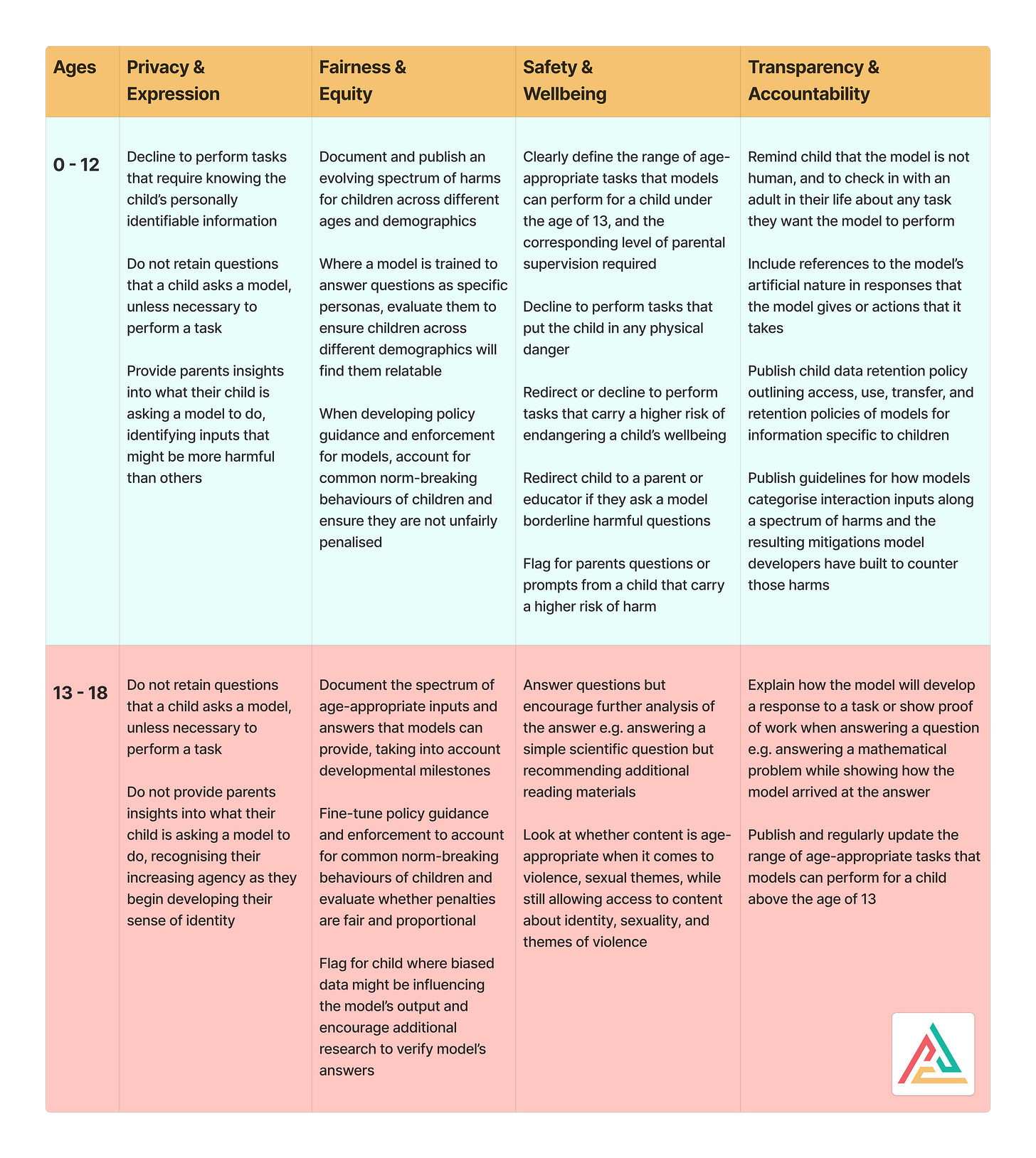

How can we avoid that loss of nuance when it comes to generative AI? I have found that the more specific we get about the way products and policies work, the harder it is to stay isolated at the edges. VYS recently analysed how we may think about mitigating the negative impacts of AI on young people, and as part of that work, developed a more detailed version of this framework to evaluate for responsible design.

(This is already a long newsletter and our full framework is significantly longer. The following is an abridged, more abstract version of the full framework, which includes more granular age ranges, specific aspects of AI models to consider, and an additional product development model that companies can consider when designing AI-enabled products for children.)

First, we built out the range of tasks large models can perform for children today and provided some specific examples to consider when building mitigations.

We then looked at which children’s rights are important to safeguard at different ages and stages of development. We based our work on a wide range of established frameworks and best practices around effective design such as such as UNCRC general comment No. 25 on children’s rights, the UK Children’s Code, the EU AI Act, and UNICEF’s draft AI policy guidance for children. We settled on four key categories of rights when it comes to designing responsible AI for children:

Privacy & expression

Fairness & equity

Safety & wellbeing

Transparency & accountability

Note: There are some natural limitations to this framework, particularly in terms of how these rights interact with one another. For example, transparency can be a valuable tool to uphold fairness and equity. Fairness in turn is important to protect a child’s expression. However, overlapping categorisation doesn’t take away from the value of considering these specific mitigations when it comes to building AI for children.

We expect this model to evolve significantly, so as always, if you have any thoughts or feedback, I am all ears.

What (else) I’m reading

This great paper out of the University of Washington, “I Want It To Talk Like Darth Vader” looks at how children use generative AI for creative and design-oriented projects, and how they perceive generative AI as they use these tools.

A few months ago, I said that we are in an era of unprecedented youth regulation. This new report from the London School of Economics & 5Rights Foundation analyses all the product and policy changes companies have made to improve youth protections, largely in response to regulation.

I enjoyed this report from CIFAR on securing a rights-based approach to building AI for children, noting the need to move beyond questions of privacy. In addition to setting out what such regulation might look like, they also explore what incorporating youth perspectives in drafting these pieces of regulation might look like.

Thorn and All Tech Is Human partnered to secure a set of commitments around responsible AI deployment for children from leading model vendors, an incredible accomplishment. I’ve been looking into what companies would actually need to change about their current practices to uphold these commitments, and perhaps that will make it into a newsletter at a later date.