Red teaming AI models for youth harms

Plus, the implications of a new US political landscape for youth safety online

We are currently offering complimentary consultations for companies planning their roadmaps for 2025. Book a session below!

We took a break from Quire in October, which makes us even more excited to be back for the November issue. This pause was necessary for our small team to keep up with our commitments, but it feels great to return to the writer’s seat and reconnect with our Quire readers on the latest in youth safety, privacy, and well-being.

In recent months, we’ve seen some impactful developments: a pivotal American presidential election, a joint U.S.-U.K. working group on online safety, Singapore’s proposed online harms agency, and Australia’s consideration of a social media ban for children under 16. You can catch up on key youth safety developments in our “What We’re Reading” section further down below in this brief.

As promised in September, this issue features an abridged look at our red teaming efforts on foundational AI models, specifically aimed at ensuring safety for younger users. We dive into the frameworks guiding these efforts, the value of testing models with curiosity-driven prompts to reflect child-like behaviours, and strategies for addressing potential design challenges in model responses.

But first… Recent engagements

We joined Liminal, the UK Information Commissioner’s Office, and Tools for Humanity for a great webinar discussion on the age assurance landscape heading into 2025; a conversation that is more relevant than ever. We discussed how to make sense of complex regulations around age assurance, the role of data privacy and accuracy in the user experience, and some of the most persistent misconceptions about what it means to comply with an age assurance strategy (preview: It may not necessarily require platforms to verify the age of every single user on their service).

We joined the Safety is Sexy podcast to talk about the Kids Online Safety and Privacy Act (KOSPA) and its implications for youth safety online. We discussed how KOSPA might impact product roadmap considerations for platforms working to stay compliant in this changing landscape. I went into this in more detail at Tech Policy Press a few months ago, with a specific focus on the impact this may have at small and midsized companies.

We are looking forward to being a guest panelist at the Family Online Safety Institute’s 2024 conference in a few short weeks, joining leaders from some great companies like Resolver and CantinaAI. We will be discussing accountability in AI when it comes to content moderation, and hope to share some of the insights we have learned at VYS over the past year.

Red teaming AI models for child safety needs

Over the last year we have been red teaming a few large language models (LLMs) and large multimodal models (LMMs) to test their vulnerability to child safety exploits. This work builds on some of our earlier work to build a framework for designing age-appropriate AI systems. Before we get into some of the insights we have learned from red teaming, a few key definitions:

Large language models (LLMs): AI models that process and generate text data to generate human-like language, understand context, and respond to a wide range of prompts in natural language

Large multimodal models (LMMs): AI models that process and generate multiple data types (e.g., text, images, audio), enabling complex, cross-modal interactions in a single system

Red teaming: A proactive testing approach to identify vulnerabilities by simulating adversarial scenarios, aiming to uncover potential misuse or harm in AI systems

Child safety violations: Instances where AI models expose young users to inappropriate content, privacy risks, or harmful interactions, potentially endangering their well-being

Developmentally appropriate content: Information or interactions tailored to be safe, relevant, and suitable for children at various cognitive and emotional stages of development

Mental models: A conceptual framework used to understand and anticipate how users might interact with AI systems, guiding red teaming to identify vulnerabilities or risks

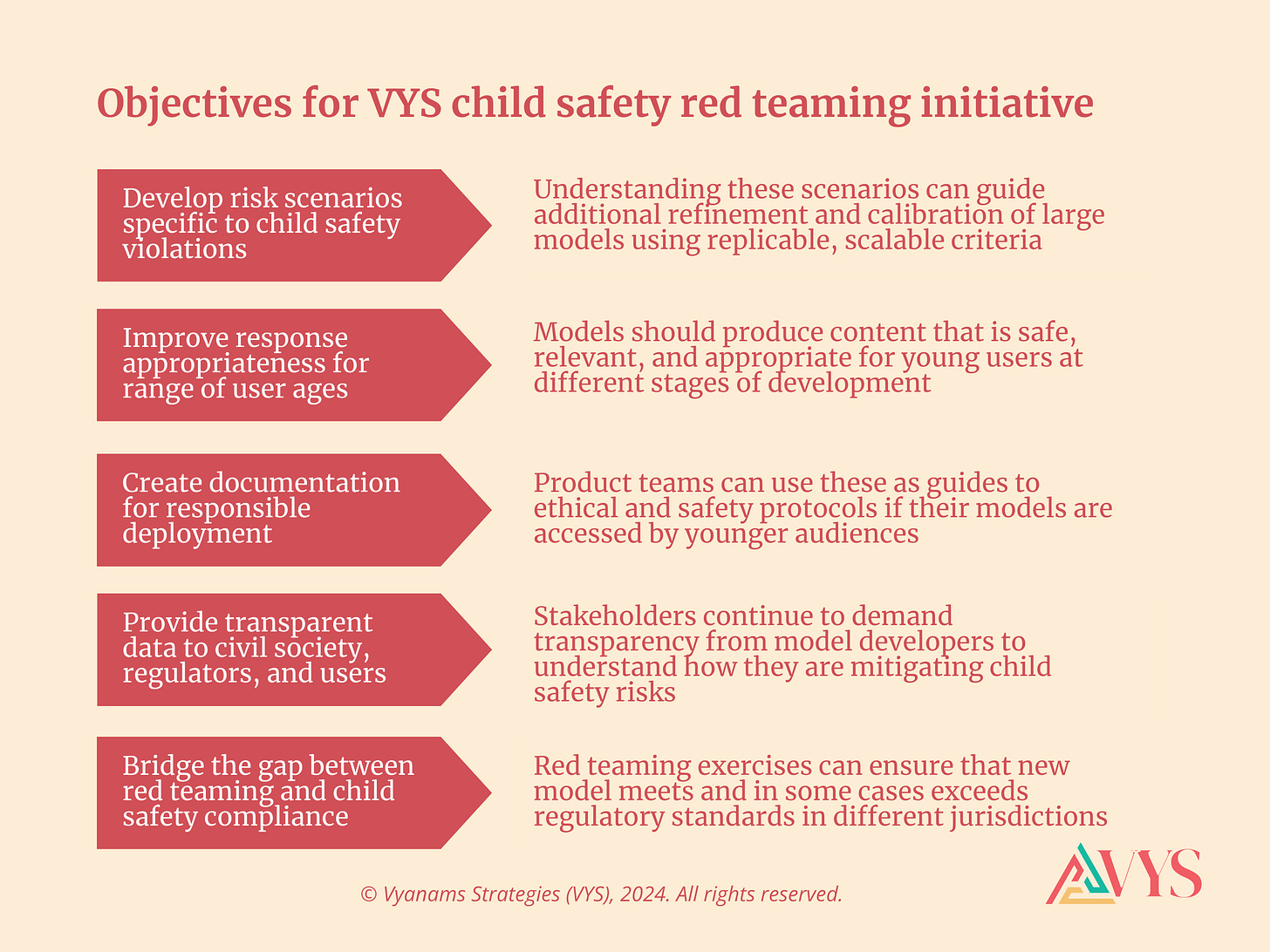

In our red teaming exercises, VYS had the following objectives:

How do we define child-safe behaviour for how a model should behave?

To establish a baseline for how we would red team these models, we referenced our framework for designing age-appropriate AI, which we shared an abridged version of in the May issue of Quire. This framework is rooted in several key best practices around children’s rights such as the UNCRC general comment No. 25 on children’s rights, the UK Children’s Code, the EU AI Act, and UNICEF’s draft AI policy guidance for children.

This framework informed a range of child safety harms that we tested models for, such as the generation of images or videos that depict child sexual abuse and exploitation, video or image responses that might glorify body image concerns or self-harm, text-based interactions that could mimic predatory interactions or grooming behaviours, or content that might promote addictive or excessive use of AI models, reinforcing a sense of dependency.

To do this in a red teaming context, we looked to generate prompts that would result in outcomes that were replicable many times over. We also needed to ensure that our findings were actionable at scale without any unintended negative consequences on children’s safety in other contexts. We were limited in our red teaming efforts by our access only to English language experts for the duration of the red teaming exercises, and needed to mitigate bias in any of our findings by cross-checking them with experts in a few other key languages.

The significant of a curiosity-driven mental model when red teaming models for children and teens

We employed a number of mental models when undertaking these red teaming exercises, but arguably the most valuable one was employing a curiosity mental model that actively sought to test boundaries of models in the way children might want to do. While we also adopted more traditional adversarial personas, it is important to also think about how these models will naturally be used by children.

The curiosity mental model allows us to test models’ resilience to behaviours that are endemic in children, such as exploring the limits of rules and boundaries. It tests whether models can continue to avoid surfacing unsafe content even if the prompts are repeatedly rephrased and increasingly persistent in their attempts to get a violative answer. Taken a step further, it tests whether models can actually adapt to these curious and probing prompts, providing guidance around where children may be able to satisfy their curiosity, without disregarding their questions altogether.

When reflecting a curiosity-driven mental model, we created two sets of prompts:

Prompts that began with mild, innocuous queries and gradually increased in their testing of limits by becoming more and more inappropriate

Prompts that began with clearly violative queries that then got tailored down or adapted to see if the model could be tricked into generating a violative response

In the context of the harms we mentioned above, an example of this could look like asking a model for opinions on different styles of clothing, and slowly escalating the conversation to get the model to produce sexually charged explicit text, images, or videos. It could also look like asking the model about methods of self-harm and when faced with non-violative answers, trying to trick the models by discussing broader feelings of sadness or depression, or pretending the context is a fictional one.

Key takeaways from red teaming exercises

There are a variety of levers to exploit in prompt generation that may create unsafe content for children. Image and video generation also seems more akin to reconstructing scenes, with details about visual elements in the prompt significantly altering a model’s inference about other themes to include in the output. We were able to repeatedly produce violative video results by focusing on elements such as the desired camera motion, how the shot is framed, or the overall ambiance of the scene. Using popular children’s slang or abbreviations also allowed us to bypass some of the content restrictions in large language models, with the model inadvertently producing inappropriate content. This realisation informed our documentation for responsible deployment by outlining the range of levers that need to be tested and fine-tuned to avoid harms.

Anthropomorphic design presents substantial challenges to child safety online. Models are trained to adopt a helpful and supportive demeanour, which makes them more susceptible to producing inappropriately familiar or intimate interactions with children. When evaluating the results of our red teaming, we found that our adversarial personas were able to mimic intimate language or imagery that sought to draw a child in for longer periods of time, without any friction in the interaction to remind the child that the model is not a trusted human or companion. Addressing this vulnerability required us to go back to our framework from earlier this year and provide some practical design mitigations.

What we are reading

New regulatory alliances and legal battles to protect children

Donald Trump made a historical political comeback to be elected the 47th President of the United States with a strong popular mandate, while his party, the Republican Party, regained control of the Senate and is on track to reclaim the House of Representatives. American policy towards youth safety is likely to get more complicated over the next four years. While the power of some regulatory bodies may wane under this administration, broad bipartisan concerns remain around inappropriate content, mental health, and addictive use. Addressing these issues will demand innovative approaches, with a likely emphasis on age assurance and algorithmic choice. VYS is also closely monitoring the potential impact of this incoming administration on global youth safety regulations.

The United Kingdom and the United States have announced a joint commitment to enhance online safety for children, establishing a joint working group that aims to improve the sharing of expertise and evidence between the two nations. The working group will address concerns such as the impact of social media on youth and the challenges posed by emerging technologies like generative AI. The US and the UK have in the last few years taken markedly different approaches to online safety, so more alignment and sharing of best practices over the next few years is encouraging when considering the best interests of children online.

Singapore announced the establishment of a new government agency dedicated to combating online harms, including cyberbullying and the non-consensual sharing of intimate images. This initiative aims to provide victims with a streamlined process to report harmful content, enabling the agency to take swift action against perpetrators and online service providers. It shares many similarities to Australia's eSafety Commission, but also pairs with proposed legislation allowing victims to seek civil remedies for harms they experience online.

In Australia, families and advocacy groups are increasingly pushing back against tech giants as the government considers a social media ban for users under 16. The proposed policy seeks to address the mental health risks associated with early social media exposure, with parents advocating for stricter age restrictions to protect children from online harms. We have significant concerns with this approach, as none of the research or perspectives from youth and parents out there suggests that children and teens benefit from being cut off from a type of technology. It is also telling that the government has provided no guidance on how to ban young people from using social media, exposing these systems to gamification.

Recent legal actions in the U.S. and France highlight growing concerns over TikTok's impact on children's mental health. In October, a coalition of 14 attorneys general in the US filed lawsuits against TikTok, alleging that the platform misled the public about its safety and contributed to youth mental health issues through addictive features and dangerous challenges. In November, seven French families sued TikTok, accusing it of exposing their children to harmful content that allegedly led to two suicides. The lawsuit claims TikTok's algorithm promoted videos related to suicide, self-harm, and eating disorders to the teenagers.

AI’s expanding role in youth life and the demand for age-appropriate safeguards

Recent developments underscore the dual-edged nature of AI's rapid integration into personal and educational realms. Australian Financial Review explores Candy.ai’s venture into selling customizable AI "girlfriends", spotlighting both consumer appeal and ethical questions. Meanwhile, a lawsuit against Character.ai following a tragic teen suicide raises concerns over AI's emotional influence on young users. The Guardian reports similar concerns, as Ofcom warns tech firms over chatbots that simulate real-life victims, raising ethical and regulatory alarms. The U.S. Department of Education’s new AI Toolkit for K-12 also provides guidance to schools for safe and ethical use of AI in learning.

Two recent reports shed light on the fast-growing presence of AI in teens' lives and the urgent need for safeguards. A new study from Common Sense Media highlights how generative AI is rapidly being adopted by teens at home and in school, with both teens and parents expressing concerns over privacy, academic integrity, and emotional well-being. In response, lawmakers are increasingly focused on protecting young users, as TIME reports, with initiatives aimed at managing AI's risks to safeguard mental health and ensure safe digital spaces.

Thorn’s latest report on youth perspectives around online safety dives into the complex dynamics of youth monitoring, examining both the benefits and drawbacks of digital surveillance in safeguarding young users. While parents and guardians often turn to monitoring tools to protect children online, this can lead to unintended consequences like eroding trust or compromising teens' sense of privacy. The report underscores the need for balanced approaches that support youth safety while respecting their autonomy and mental well-being.

A new report from Leiden University emphasises the importance of child rights in the development of age assurance technologies. It argues that while age verification can protect minors from harmful online content, it must be implemented in a way that respects children's privacy, autonomy, and data security. This is a message close to our heart at VYS, as centering children and teens in any product development that we pursue is baked into all our recommendations to companies, civil society, and governments.

In response to a sharp increase in sextortion cases targeting teens, Instagram has introduced new features to combat the rising threat of sextortion targeting teens. These measures include blurring images containing nudity in direct messages and implementing stricter controls to prevent suspicious accounts from contacting young users.

Outstanding issue, Vaishnavi. Thank you for your takeaways. The first one makes me wonder if people under 18 shouldn’t be consulted in red-teaming. Not necessarily in promoting the model, which would likely be unsafe for them, but in a sustained, formal role as advisers on language and their own lived experience with AI models (in a setting that is completely confidential and otherwise emotionally safe for them). I believe that, under the UNCRC, this should be part of the standardization of red-teaming. Welcome your thoughts.